The post The RunSafe Security Platform Is Now Available on Iron Bank: Making DoD Embedded Software Compliant and Resilient appeared first on RunSafe Security.

]]>The challenge for defense programs is that meeting these requirements, particularly for embedded systems, often results in increased labor and difficulty in getting tools approved and deployed.

That’s why we’re excited to share that the RunSafe Security Platform is now available on Iron Bank, the DoD’s hardened repository of pre-assessed and approved DevSecOps solutions.

As a verified publisher, RunSafe provides DoD software development teams with access to Software Bills of Materials (SBOM) generation, supply chain risk management (SCRM), and code protection through an ecosystem they already trust.

Why Iron Bank? A More Secure Path

Iron Bank is built to help defense programs quickly deploy new tools without spending months navigating approval processes. Every product listed on Iron Bank goes through rigorous security assessments, container hardening, and compliance validation. Because the containers are scanned daily for vulnerabilities, DoD teams gain access to resilient tools that keep the software supply chain secure and get software to deployment faster.

With RunSafe listed as a verified publisher, DoD teams and integrators can now pull down the platform directly from Iron Bank, making it easier for defense programs to integrate and use.

What RunSafe Brings to Iron Bank

The RunSafe Security Platform addresses some of the toughest challenges in embedded software security. Here’s what you can access through Iron Bank:

C/C++ SBOM Generation

RunSafe provides the authoritative build-time SBOM generator for embedded systems and C/C++ projects. Automating SBOM generation is critical for meeting DoD requirements, especially for unstructured C/C++ code where traditional SBOM tools fall short.

Supply Chain Risk Management

SCRM capabilities enable DoD teams to take action, not just generate a static SBOM. Teams can monitor for new vulnerabilities and check license enforcement and provenance. With a complete, correct SBOM, teams can implement required SCRM practices.

Runtime Code Protection

RunSafe hardens binaries against exploitation through moving target defense (e.g. Runtime Application Self Protection (RASP)), defending weapons systems at runtime to increase resilience. This resilience applies to future zero days as well, providing fielded weapon systems protection between software upgrade cycles that can be two years apart.

Accessing the RunSafe Security Platform on Iron Bank

If your program is working to modernize DevSecOps practices, automate SBOM generation, or secure embedded systems without code rewrites, RunSafe is now available directly on Iron Bank.

You can find our containers by logging in and accessing the Iron Bank repository here.

Request a consultation to learn more about the RunSafe Security Platform and Iron Bank.

The post The RunSafe Security Platform Is Now Available on Iron Bank: Making DoD Embedded Software Compliant and Resilient appeared first on RunSafe Security.

]]>The post Don’t Let Volt Typhoon Win: Preventing Attacks During a Future Conflict appeared first on RunSafe Security.

]]>For a deeper discussion on Volt Typhoon’s tactics and the national security stakes, listen to our RunSafe Security Podcast episode featuring experts unpacking the threat to critical infrastructure.

Unlike with ransomware attacks, Volt Typhoon’s aims are focused on the long-term, not the short-term. Ransomware culprits want quick transactions with only enough disruption to their targets as required to extract payments. Nation-state aligned cyber offense, however, has a two-fold purpose: (1) blunt military capabilities and (2) create disruption and overall panic in society.

These actors take a long-term perspective, preparing in advance to be able to achieve both goals when a conflict arises. In the case of the PRC-backed Volt Typhoon, that conflict could be the PRC’s attack on Taiwan. If Volt Typhoon is effective in meeting its goals, it could impact the response of the United States, potentially deterring the US from engaging in the conflict. We are in an age of cyber as a means to achieve geopolitical goals.

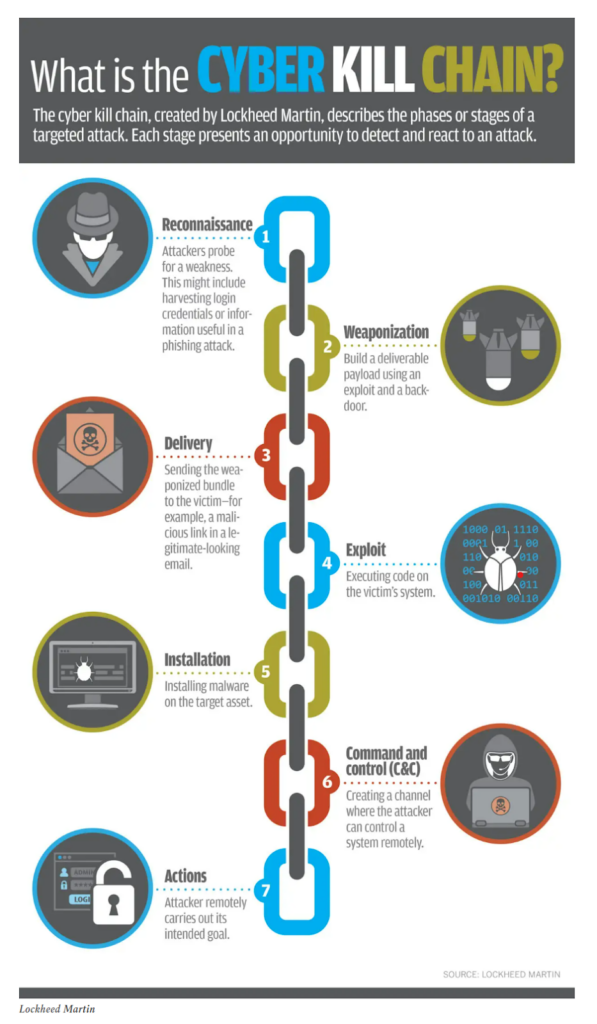

What Is the Cyber Kill Chain? How Nation-State Actors Prepare for Attack

The Kill Chain construct originates in kinetic warfare. For example, in 1990, General John Jumper coined a kill chain for airborne targets: F2T2EA (find, fix, track, target, engage, assess). It is expected to be completed as rapidly as possible. Cyber kill chains, on the other hand, can occur over a much longer period of time.

In the cyber kill chain coined by Lockheed Martin, Reconnaissance is the first phase before Weaponization. The Reconnaissance phase can be prolonged; it is also referred to as the preparation of the battlefield stage. The attacker is in the system, searching for weaknesses, and in some cases living off the land.

Volt Typhoon is in the Reconnaissance stage within critical infrastructure, preparing to move to the next stages of the kill chain if geopolitical circumstances warrant.

What Does a Volt Typhoon Cyber Kill Chain Look Like?

The Department of Homeland Security’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) has published detailed descriptions of the typical pattern of attack involving Volt Typhoon. Drawing from a February 2024 CISA notice, a Volt Typhoon cyber kill chain typically involves:

1. Extensive pre-compromise reconnaissance

Surveillance starts by profiling network traffic into and out of a target organization. The goal is to identify:

- Hardware at the edge: By identifying hardware at the edge and the OS versions on the hardware, the attacker can plan the cyber weapons they need for the next stage of the attack. The makes, models, and configurations of routers and other edge devices can often be determined by careful observation of in-bound and out-bound traffic.

- Communications protocols: Communications protocols provide insight into the make, models, and configurations of other devices, further inside a target network.

2. Exploitation of edge devices using known or zero-day vulnerabilities

Compromising the edge devices of a target network is important, because often those edge devices are configured to provide alerts when indicators of compromise occur. By compromising the edge devices themselves (routers, etc), the attacker can “blind” the sensor network. Exploitation will target the operating systems and applications on the edge devices. Once edge devices have been compromised, those devices themselves become part of the surveillance network, but with a privileged view of behavior “inside the network.” Volt Typhoon has used a wide variety of exploitation techniques:

- Memory safety exploitation: In one confirmed compromise, Volt Typhoon actors likely obtained initial access by exploiting CVE-2022-42475 in a network perimeter FortiGate 300D firewall that was not patched. There is evidence of a buffer overflow attack identified within the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL)-VPN crash logs.

- Web-based exploitation: Some edge devices have poorly configured management interfaces, which can expose administrative functions to the Internet.

3. Obtaining administrative credentials using privilege escalation vulnerability

Using the privileged position on edge devices, the attacker tries to determine administrative credentials so that further access to devices will no longer require the exploitation from step 2 above. Utilizing credentials also means that the attacker can maintain persistence on a device, even if the exploitation vector from step 2 is patched.

4. Moving laterally to the domain controller, using the stolen credentials

Compromising the domain controller is a key objective, because it means that all further accesses will have the patina of legitimacy. Identifying fraudulent logins from legitimate user names and passwords requires sophisticated tools that most organizations don’t use.

5. Discovery on victim network, using Living-off-the-Land (LOTL) techniques

With “domain controller” access, the attacker now moves into the stage of executing their mission on target, which might be:

- Exfiltrate data: Often the objective of an attacker is to to steal sensitive data (e.g. medical records, financial information, corporate intellectual property, government classified information). The attacker will be able to patiently find where that sensitive data is located and craft a plan for low-probability of detection exfiltration of that data.

- Inject tools for direct action: This could mean placing assets for ransomware attacks or disruption of system services. Extensive documentation has highlighted the PRC’s commitment to disrupting US critical infrastructure in the event that China attempts to retake Taiwan.

What Can Be Done Today to Prevent Volt Typhoon’s Future Success? Addressing Memory Safety

The attack scenario above highlights that a memory safety vulnerability is part of the Volt Typhoon cyber kill chain. It’s a reasonable approach as: (1) a number of the most dangerous CWEs per MITRE relate to memory safety (6 of the top 25); (2) 70% of Google and Microsoft security patches relate to memory safety as referenced in NSA’s advisory about memory safety; and (3) in VxWorks Urgent/11, 6 of the 11 vulnerabilities related to memory safety.

It is reasonable to hypothesize that Volt Typhoon cyber kill chains also target OT/ICS devices, which are attractive as both edge devices (step 2 above) and as controllers of critical infrastructure. Capture of these devices enables Volt Typhoon to directly disrupt critical infrastructure by sending malicious commands and/or erroneous data to these devices. Additionally, these OT/ICS devices are often good pathways into the IT infrastructure.

In the case of an attack on Taiwan, Volt Typhoon could deter the US from taking action by exploiting a memory-based vulnerability, for example, to disrupt a major power grid.

Approaches do exist for memory safety now, including the hardening of software in OT/ICS devices to withstand attacks against both known and unknown memory-based vulnerabilities. Unlike static defenses that can be easily bypassed, techniques like moving target defense randomize at a granular level the memory layout of software binaries. By constantly shifting the software landscape, attackers are unable to predictably exploit memory vulnerabilities.

For example, RunSafe Security’s Protect solution mitigates cyber exploits by dynamically relocating software functions in memory every time the software is loaded. By ensuring that the memory layout changes every time software is loaded, RunSafe effectively thwarts repeated attack attempts and prevents bad actors, like Volt Typhoon, from compromising critical infrastructure.

Call to Action for Critical Infrastructure Owners

As outlined, there is time to foil Volt Typhoon’s Exploit stage and their ultimate goal of impacting the United States response if a conflict arises. Only critical infrastructure owners can close the gap—by demanding Secure by Design systems and insisting on runtime protection against memory-based exploits.

Unlike CISA, which provides guidance and recommendations, critical infrastructure owners purchase and update ICS/OT devices installed in their plants, grids, and factories. It falls in their hands to require, demand, and pound the table for ICS/OT device manufacturers, who are their vendors, to increase the cyber resilience of embedded devices. These devices must have the ability to operate through attacks in real-time without the need for human, centralized monitoring and response.

By demanding memory safety and other defense measures from their ICS/OT device vendors now, critical infrastructure owners can prevent the success of Volt Typhoon in the future.

Want to hear from RunSafe leaders on how to approach this challenge? Tune in to the RunSafe Security Podcast episode on Volt Typhoon to explore real-world implications and actionable strategies.

Learn more about RunSafe Security’s Protect solution in our technical deep dive.

The post Don’t Let Volt Typhoon Win: Preventing Attacks During a Future Conflict appeared first on RunSafe Security.

]]>